History on Ice: 25 Years of Ice Harvest Celebration at Three Rivers

By: Andy Sima

January 18, 2023

Category: History

Due to poor ice conditions, our 25th Annual Ice Harvesting Day on Saturday, January 21, is cancelled. We’re very sad the event is cancelled, but we invite you to stop by Richardson Nature Center from 10 AM–2 PM to check out our ice harvesting exhibit and display of tools, warm up by a bonfire, and enjoy free kicksledding demos on the trails.

Barely 100 years ago, Minnesota was a dominant force in a global industry, with our state shipping more than 20 million tons of product every year. Yet today, this business has melted into nothing. What kind of business could just disappear practically overnight?

The answer: ice.

Once a critical resource to keep food refrigerated in homes and on train cars, eventually the spread of mechanical refrigeration made ice harvesting obsolete.

However, not every trace of Minnesota’s ice harvesting empire is gone.

For the last 25 years, staff and volunteers at Hyland Lake Park Reserve's Richardson Nature Center have shared the tradition of ice harvesting with its annual ice harvest event. Thousands of visitors have learned about the science and history of ice harvesting by getting hands-on with ice. And every year, people come back for more of the unique experience.

The Importance of Ice

Cold has always been critical to keep food fresh, and using winter’s natural resources was a common practice across centuries and continents.

Minnesota’s abundant lakes and rivers, combined with freezing temperatures, made for ideal ice-harvesting conditions. It was common for farmers throughout Minnesota to cut ice on their own ponds and save it throughout the year to keep food fresh. Ice was also industrially harvested from Minnesota’s frozen lakes mainly for the purpose of selling it throughout the Midwest or loading it onto train cars to refrigerate food. The industry peaked around the late 1800s and early 1900s, but it existed from the 1800s to the 1950s. Shady Oak Lake, on the Minnesota River Bluffs Regional Trail, had one of the largest ice houses west of Chicago, and almost all of it was for the railroad. (Learn more about the ice harvest industry in this blog post.)

"Ice harvesting, possibly at Bass Lake, The People's Ice Company," courtesy of Minnesota Historical Society.

This rich history is part of why, in the late-1990s, an event was created at Three Rivers Park District that would bring the connection to wintry resources alive.

The Beginning

In 1998, a park visitor named Tim Graf attended Hyland Lake’s Winterfest, a previously held winter recreation festival, and was surprised to find that the ice harvest station was just one saw and a hole in the lake. Tim, whose grandparents owned an ice business in the 1930s, knew there could be more.

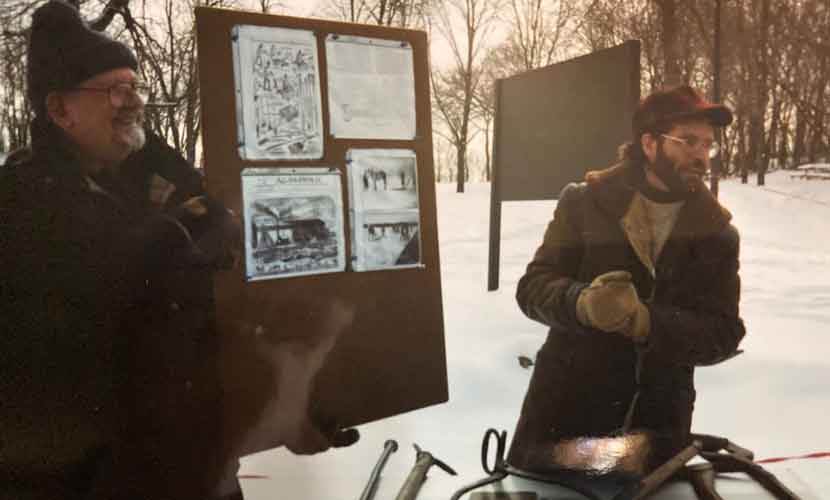

To discuss the possibilities of expanding the ice harvest experience, he met with staff running Winterfest. Both Tim Anderson, an outdoor educator, and Jane Votca, an educator at Richardson, saw the possibility of an exceptional outdoor educational opportunity. Combining their passion and creative energy with Tim Graf’s knowledge, stories and tools, and the numerous volunteers and staff from Three Rivers, the single saw and a hole in a lake expanded to the hands-on learning event it is today.

The first annual ice harvest event began in January of 1999 at Hyland Lake. Due to poor weather and a slushy lake in '99, January 2000 marked the first time a real ice block was cut for the event. The event saw more than 500 guests.

Ever since those first years, the event has been an opportunity for people to interact with winter in a rare way. Standing on a frozen lake, visitors drag plows to carve out where to cut. Using saws, visitors cut blocks of ice free from the lake. Event staff then guide floating cubes through open channels of water and visitors haul them onto land. Once out of the water, visitors use dozens of genuine ice harvest tools to shape, experiment on and play with the ice.

An Event Evolution

Every year after the event, Jane and the Richardson team met with volunteers to discuss how to refine and improve for next year. Early versions of the event included ice fishing, ice sculpting, skijoring and snowshoeing. Over time, the event has shifted its focus from ice in general to include more about ice harvesting’s history and science. This lets visitors follow the whole ice harvest operation from plowing, to cutting, to harvesting, to weighing, to shaping, and even to storage. Other activities, like kicksleds, food preservation demonstrations from the Park District’s historical interpretation (complete in 19th century clothing), and mock water rescues from the Bloomington Fire Department, have stuck around.

The event has shifted locations as it has developed, too. After a few years of sharing the Hyland Lake ice with ice fishers and cross-country skiers, the event moved to Turtle Basking Pond, where ice harvest activities could be the main focus. Starting in 2014, Turtle Basking Pond hydrology changed, causing its ice to thaw in the wintertime. This made it unsuitable for the event, so the event moved to the nearby Wood Duck Pond.

Pulling the event together requires many different hands. Volunteers, like Dale Eggert, have donated their ice-harvesting tools and time to join the Richardson crew. Besides being enthusiastic teachers for guests, volunteers also monitor ice thickness throughout the winter. The Hyland maintenance team supports the event, with the park carpentry team even building an ice chute based on Tim Graf’s design. First used by the Richardson crew at the 2005 event, this simple machine eases the process of getting ice out of the lake by combining a lever and a ramp, allowing the ice to be pulled out of the water rather than lifted. It is still used at the event today.

Every year offers many ways for visitors to build a connection to the ice. As everyone participates in the ice harvest together, families and individuals build their own Minnesota stories — sometimes with people who are experiencing a Minnesota winter for the very first time. Visitors love getting hands-on with Minnesota history, and many come back every year to experience a unique winter activity that is rarely done anywhere else.

Schools are also a big part of the event. Since 2005, Richardson has also invited local classrooms to a special school-day ice harvest. Students are empowered to learn by using hands-on tools, and the kids are always thrilled by their “most dangerous” field trip.

Losing Winter

As the event has changed, so has the climate. During the height of the ice industry, and for centuries before that, it was common to have 16 to 18 inches of ice on a lake by the first week of January. Nowadays, that isn’t so common. Of the event’s 25-year run, at least 10 of those years have had ice thickness below that. 2022 saw only 7 inches of ice for the day of the event.

Dedicated staff and volunteers continue to adapt the program by limiting the number of people on the ice, moving demonstrations to land, or bringing in blocks of ice from elsewhere. For 2023, the 25th anniversary event couldn’t be on the ice at all due to warm temperatures and rain that created poor ice conditions. Though the main event was cancelled, people are still invited to learn more about ice harvesting through an exhibit and display of ice harvesting tools at Richardson Nature Center.

The changing climate doesn’t mean the end of the recurring ice harvest event, but it is indicative of larger, global changes. As greenhouse gases, deforestation and other factors increase the average global temperature of the planet, the world warms and weather becomes more unpredictable.

In Minnesota, we are already seeing increased flooding, longer and hotter dry spells, and warmer summers. But, as shown over the years of our ice harvest, it’s the warming winters that are of huge concern. Our winters are warming faster than almost any other state in the country, and winter minimum temperatures may be as much as 10°F warmer by the end of this century.

Minnesota has already lost an average of 10 to 14 days of lake ice over the last 50 years. This is having dramatic effects on industries that are reliant on winter, like snowmobiling or skiing or snowshoeing, but also can be detrimental to fish populations and animal habitats. (Learn more about how the climate is changing Minnesota’s ecosystems from the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources.)

This is why a key component of the ice harvest event is now education about climate change. Education is one of the most effective tools for building actions that can mitigate and adapt to climate change. Seeing melting ice is an effective way to visualize a global problem on a small scale. Richardson has even found creative ways of visualizing climate change, too. One year, they contracted an artist to produce ice sculptures to show them melting under different climates. This even attracted the attention of famous polar explorer and climate activist, Will Steger, who runs his own ice-themed events near Ely, Minnesota.

The relevance and excitement of this program remains important, even if it can’t always be on the ice. Thanks to the hard work and dedication of people like Jane Votca, Tim Graf, Tim Anderson, other volunteers like Dale Eggert, the staff at Richardson, the Hyland maintenance team, and so many more who have made those last 25 years possible, we’re able to make education both accessible and engaging for visitors of all ages.

Special thanks to volunteers Dale Eggert and Tim Graf, and Kimi Aisawa Romportl, Adam Barnett, Pauline Bold, Janet Christiansen, Katie Frías, Allie Gams Beeson, Michael Gottschalk, Heidi Matheson, Kari Peterson, Valerie Quiring, Monica Rauchwarter, and the rest of the Richardson Nature Center staff for helping prepare this blog.

About the Author

Andy Sima worked as a historical interpreter at The Landing, before moving to Sweden to attend graduate school in Landscape Ecology. His favorite building at The Landing was the old wooden one. He previously worked as a seasonal naturalist at Baker Outdoor Learning Center and at Philmont Scout Ranch. He loves birds and hiking and writing and sometimes enjoys writing about hiking and birds. Sometimes he makes maps. His favorite bird is, currently, the barred owl.

Related Blog Posts

Ice Harvesting

By: Tim Graf

Have you ever wondered how food and drinks were kept cold in the years before electric refrigeration? Learn more about the history of the ice harvesting industry and try it out for yourself at Ice Harvesting Day on January 26.

Winter Solstice: Stories and Traditions From Around the World

By: Michelle Bierma Tim Reese

Winter solstice falls on December 21 and marks the shortest day of the year. Discover solstice stories told around the world and explore ancient celebrations honoring this magical time of year.

Have you ever wondered why we “deck the halls with boughs of holly” each December or why we light Hanukkah menorahs on midwinter nights? Read on for more about the unknown stories and history behind some of our holiday traditions.